New Exercise and Fitness Review

A

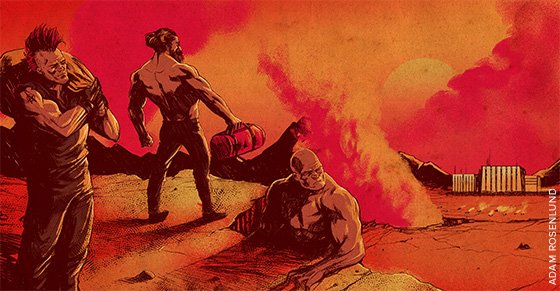

fter they escaped, the prisoners ran, scrambled, stumbled across the heat-baked tundra. Two hours later they reached the first rise beyond the prison. From their elevated vantage, they looked back and saw their lead pursuer’s vehicle plummet through the dry mulch, sending him into a deep pit. Dust rose. Several seconds later it was followed by a geyser of fire, fueled by methane that had been trapped for millennia. The column of fire continued to burn as the guards in the other vehicles turned back toward the prison.

The three men headed west for two days instead of making the obvious turn to the north. While they were almost certain their guards no longer pursued them, they took every precaution. Finally, they arced toward the balmy North Shore of the Arctic Ocean, walking single file. The first man tested the ground with a walking stick to avoid falling through the porous scrub of thawed tundra. Over the past decades the earth had conspired with the climate to create death plunges for any who dared to cross, farting flammable prehistory into the atmosphere.

Now, the ex-prisoners trudged unchallenged as they crossed the hot, vast wasteland. They carried supplies cobbled together from the prison infirmary and mess hall: large skins full of water, bandages, tarps, mesh to shield their faces during dust storms, two heavy bags of sun-dried caribou strips, and a modest supply of flat black bread. Their escape had been months in the planning. They’d had the time, imprisoned without end.

The Philosopher had never been tried for a specific crime, never been given a sentence, only a judgment: guilty. No one could tell him how long he would be incarcerated or why, including his guards. Over the years, he watched as his imprisoners died or deserted, their lives only marginally better than those they supervised. The rank of guards reduced while the number of prisoners grew. The New Order found new guards much harder to come by than additional prisoners.

The Philosopher bided his time, numbers turning in his favor.

By the time the Anarchist arrived, manacled and seething with rage, his hair and eyes wild, the Philosopher had already been incarcerated for several years. The Idiot preceded both, guilty of the New Order’s greatest crime: idiocy, an inability to articulate the new laws on demand. In the cell adjacent to the Philosopher’s, the Anarchist remained silent for several weeks despite the Philosopher’s attempts to engage him.

One day, the Anarchist finally spoke. “How long you been here?” he barked, his voice rough from disuse.

“Eight long days.” The Philosopher lay on bedding stuffed with tundra thatch, hands clasped at the back of his head, elbows splayed open.

“Eight days?” Even from distance, the Anarchist’s derision carried the odor of bad breath. “I’ve been here longer than that.”

“The Philosopher bided his time, numbers turning in his favor.”

The Philosopher explained: Each summer the top of the planet tilted toward the sun. Light and heat pounded the tundra; the sun spun around the northern sky, never sinking. Water was scarce, food hard to come by, the heat intolerable. The terrible “long day” lasted more than three months, and the concrete and iron prison held on to the heat like a miser stockpiling gold. Then, with the approach of autumn, the sun arced lower and lengthy sunsets eventually turned to twilight, offering a balmy respite.

“When you’ve been here as long as I have you only count the long days,” The Philosopher said.

Before he escaped with the Anarchist, the Philosopher witnessed two additional long days blaze above the horizon.

O

n the third short day after their escape, the refugees found a subterranean shelter free of noxious methane as the heat neared its peak. They lowered themselves into the ground and pulled dusty chunks of firm thatch over the entrance, shading them during fitful sleep.

When they reemerged, the late summer sun had lowered, radiating bronze and orange at the western horizon. The sun was so large that, squinting at it, the Philosopher thought he could see individual licks of fire leaping from its surface. The three men packed their belongings and began trekking north. The Idiot carried a full bag of caribou meat in each hand.

“You should carry that on your back,” the Philosopher suggested.

The Idiot had hands the size of an orangutan’s. He didn’t answer or offer his customary grunt as he clutched the handles of the bloodstained burlap bag in his ferocious paws. The other two didn’t complain: The Idiot carried more weight than they did.

All the men packed their own supply of water. Other than their food, the Philosopher and the Anarchist carried all of the group’s supplies over their shoulders, leaving their hands free. The Philosopher knew the Idiot was stupid, but keeping his full hands meant that he couldn’t lead with the walking stick, decreasing his chance of falling into the earth.

When they had been incarcerated, the guards allowed the inmates time to exercise in the small basement gym, stocked with neglected iron plates and bars. The room smelled of rust and the sweat of the dead. On days when the guards were inclined, they took the prisoners to the gym and locked them in the room for an hour or two. The room was dark and oppressively hot. The barred window near the ceiling provided slits of light, and it took the Philosopher a few minutes to adjust to the heat and darkness before he could negotiate the room.

He never missed a session in the gym, focusing on building even more muscle mass, planning to use it when he had the opportunity.

Soon after the Anarchist first spoke to the Philosopher, he started taking advantage of these occasional trips to the gym, too, seeing anarchical purpose in lifting heavy metal. The Idiot always accompanied them, but all he did was clench a heavy plate or dumbbell in each of his enormous hands, trudging back and forth along the far wall. His head never wavered, focused only on what lay directly in front of him. For the entire duration of the prisoners’ time in the gym, the Idiot performed his odd march, clutching heavy weights until the guards, lazy from their own hopeless lives, finally unlocked the door and took the prisoners back to their cells.

Out on the tundra, the men rarely spoke, saving their energy for walking and sweating, only stopping for 10-15 minutes after they had walked for three hours or more. On a break, they found shade behind a hillock as the sun hit the peak of its circular sine wave, and they each ate a couple bits of dried caribou from the Idiot’s burlap sacks. Then they resumed their journey.

“What do you think the North Shore looks like?” the Philosopher asked after they’d been walking for a while. The Anarchist was startled. At first, the Philosopher thought he was puzzled by the question. Then he realized it was the loudness of his voice in the solitude of the northern expanse. Based on their direction and how the sun rotated overhead, he estimated that they had escaped about eight days before. But it was hard to tell. They still had more than half of their water supply. That was a more important marker than time or distance.

“He never missed a session in the gym, focusing on building even more muscle mass, planning to use it when he had the opportunity.”

“How should I know?” the Anarchist grumbled.

Few prisoners had escaped since the Philosopher had been hurled into his cell, breaking his clavicle on the metal bed frame. The remaining captives thought the few who had escaped headed north because, it was believed, the polar melt had created a lush paradise along the newly formed North Shore. Northern-running fresh-water streams fed verdant meadows, and new-growth forests edged virgin beaches, abundant with succulent fruit, plentiful wildlife, and nubile women. This had been the favorite topic among both the guards and prisoners. Even the Idiot’s thick gaze turned to the others when they discussed the bounty of the North Shore.

The Idiot’s interest helped convince the other two that he should accompany them.

“We need a third man to make sure we get there,” the Anarchist had explained.

“Unh,” the Idiot replied.

The Philosopher realized the Idiot understood their plan when he availed himself of every task they instructed him to perform, stealing supplies and stockpiling them in the gym when the guards weren’t watching.

A

s they continued to head north, the landscape became rockier, a geological shift in terrain from the gray straw, gaseous decomposition, and infirm terrain. The sun had circled at least eleven 11 times overhead, and now the three men stumbled and slid on the scrabble of rising and falling ridges. But at least they no longer feared plunging through the hollow earth. A mountain range cut across the horizon to the northeast, explaining the solidity of the ground beneath them. The formation appeared immutable despite its dynamic geological thrust, imperceptible to creatures with lifespans of mere decades.

“What did you do?” the Philosopher asked the Anarchist in the dungeon gym one day. Neither helped the other during their workouts, each disdaining the other’s style of training. The Philosopher disapproved of the way the Anarchist took long rests between sets, only to heave as much weight as he could for a mere rep or two. This was an incredible waste of the time they were allowed in the gym. The Philosopher knew this was no way to build muscle, essential for life outside their prison.

“What did I do?” the Anarchist asked, puzzled.

A moment passed before the Philosopher realized the Anarchist hadn’t understood his question. The Philosopher was guilty of having conversations in his head that he thought others were privy to.

“Why were you sent here? What was your crime?”

The Anarchist didn’t respond. He clanged an extra plate onto each side of the barbell positioned on the floor. The lanky sinews at the base of his back and legs were more visible than they had been when he was first incarcerated. The Anarchist looked as though he was training to tear the prison apart.

Ignored, the Philosopher performed another set, feeling the stretch and contraction in his chest. He had squirreled away several pieces of black bread and dried caribou, and he was able to consume a portion of this stash after his workouts. A plump young guard provided him with these extra rations, fawning over his physical attributes and intellectual prowess.

The Anarchist lifted the heavy weight twice and set it down. He answered the Philosopher’s question several minutes later. Prison conversations had their own pace. “I committed acts of disobedience against the New Order. I worked at a sentencing center. After a verdict was handed down, it was my job to deliver the guilty to the detention center or to the gallows. No one followed up after the judgments. I rewrote the sentences based on my assessment, sometimes setting the guilty free, sometimes sending the absolved to prison or the gallows.” The ropy muscles of the Anarchist’s lower back strained so hard that they looked as though they might snap. “Eventually, they caught me.” He turned toward the Philosopher. “What did you do?”

“The Philosopher was guilty of having conversations in his head that he thought others were privy to.”

“I wrote an underground pamphlet condemning the New Order.” The Philosopher felt he had found common footing with the Anarchist, allied against the government. “When they discovered my printing press, I was found guilty of philosophical treason. I’m still awaiting trial.” The Philosopher performed an additional set while the Anarchist took another long rest. He felt his pectorals engorge with so much blood they ached. He clanged the barbell back onto its resting place, and he stood, pumping even more blood into the muscles of his chest to intensify the sensation. “What would you have done if I had come through your sentencing center?”

The Anarchist stopped before bending over to take hold of his barbell. He looked toward the Philosopher. “I would have sent you to the gallows.”

The Philosopher let out a hollow chuckle, but then he saw the Anarchist was serious. “But why?”

“Men who do nothing but muse and scribble against evil are complicit.” The Anarchist gripped the barbell and yanked it off the ground. The barbell held more weight than the Philosopher had ever seen him lift. He performed several reps, the plates crashing into the crumbling cement after each rep, sending up puffs of dust visible in the sunlight that seeped in through the barred window above.

When The Anarchist finished, the two men stared into each other’s eyes, but neither spoke. The cloud of dust dissipated.

A

s they headed north, the meat packs the Idiot carried grew emptier, but the Philosopher couldn’t convince him to carry anything more. The Idiot had made it clear that he would lug meat and his own water supply, and that was all he would do.

The weather had been dry and still since they’d made their escape. They’d seen few dust storms and only random plumes of methane fires. A few days earlier they’d come upon a rank stream where they’d been able to add to their water supply, straining liquid from putrescent sludge through burlap; then they boiled the blackened fluid before they poured into their empty skins.

The Anarchist often stopped and squinted at the horizon, his vision improved by stillness. The Philosopher knew what the Anarchist was looking for: not the North Shore, but caribou. Accustomed to foraging on solid, barren land, the herds remained plentiful. The thawed tundra had driven their predators to extinction, but the antlered beasts innately avoided thatched earth. They found plenty of sustenance on rocky ground.

The Philosopher had never seen the other large animal species that used to live in the north likebears, seals, deer. Infrequently, small flocks of birds flew overhead, their migratory patterns difficult to reprogram and thus their number greatly diminished. The human population was even more drastically reduced—no one could say by how many. Based on how long he had been imprisoned and the lack of communication across the globe, the Philosopher had little idea of what had died and what remained.

While caribou thrived, they were also susceptible to tundra madness, a slow-acting illness that had devastating consequences for the beasts and humans who consumed their tainted flesh. The Philosopher had watched the Traitor die, two cells away, cursing and chewing on his forearms and calves, spitting bits of his bloodied flesh onto the floor. The New Order despised traitors more than other criminals, considering the gallows a light sentence. Instead, traitors were held in their cells and given no sustenance except diseased caribou meat. They had their choice of dying of starvation or madness.

After several days of following the mountain range, the ground beneath the three men changed back to the dense tundra thicket with all the dangers of plummeting into pockets created by melted subterranean ice. They returned to walking single file, the first prodding the ground ahead. It was slow going.

The Philosopher tried to keep track of time. His assessment was that they had been out of prison for about eighteen 18 days. As the season progressed, counting became easier as twilight and, eventually, a short period of darkness settled over the land.

B

efore they’d escaped from the desolate compound, the Anarchist and the Philosopher had agreed that they could not, in all probability, carry enough food and water to survive. The trip might take them more than two months under the best of circumstances. They didn’t know how close the rising ocean had brought the North Shore. The food and water they carried might not be enough to get them to their destination. They would probably need to replenish both. The Anarchist pilfered a handgun from the armory, and the Philosopher allowed the fat young guard to caress his muscles in exchange for a small stash of bullets.

By agreement, the Anarchist and the Philosopher each held their contribution. The Anarchist also carried a hunting knife, a prized possession he had reclaimed from the warden’s office just before slitting the man’s throat. The Idiot carried no weapons or personal possessions, only the meat sacks and his water skin. The supply of bullets— seven—was so low that the Philosopher and the Anarchist had agreed they would use them only by mutual consent. The Idiot was unaware of their firepower.

As they made their way onto the unending stretch of tundra ahead, the Anarchist turned back toward the south, making certain they hadn’t passed a caribou herd.

“No luck,” the Philosopher said.

“We’ll be fine. We still have our good-luck charm.” The Anarchist tilted his head toward the Idiot.

The Philosopher looked away, back toward the bright orange, deepening blue horizon. The Idiot continued his steady pace, confident the others wouldn’t fall behind. As the Idiot’s bags grew lighter so did his value.

“We’ll find something before we run out,” the Philosopher said. He reached behind him and touched the bottom of his own pack, where he could feel the seven smooth bullets rubbing against one another. He pulled them out, slipping them into his pocket to keep them close. Later, he moved them back into his bag.

“The trip might take them more than two months under the best of circumstances.”

The Philosopher didn’t trust the Anarchist, but at least their objectives were the same. They had discussed their plan between sets in the prison gym. The two men constructed a checklist of what they needed to survive on the tundra: a gun, bullets, tarps, tools, burlap sacks, the ability to make fire and, most elusive of all, food and water. “We’ll also need a third man,” the Anarchist said.

“We do?” The Philosopher believed another person would complicate their escape.

“For the most basic reason,” the Anarchist said.

“Of course.” The Philosopher wasn’t sure what the Anarchist meant. But he didn’t want to appear stupid or naïve. And he didn’t want to be excluded from the plan. “How about him?” the Philosopher asked, indicating the Pervert, who sat on the thigh abduction machine with his legs splayed open for long holds during every rep . The Pervert was the fourth man in the cellar gym, and the only other prisoner to join them regularly during allotted workouts. A couple others, the Thief and the Arsonist, no longer joined them. Each had lost his enthusiasm for prison workouts. The Philosopher believed this was because the Thief had already stolen everything he wanted from the gym, and the Arsonist found the equipment less flammable than other parts of the compound.

“Him? He won’t do at all.” The Anarchist snorted. The Pervert was old and scrawny, not half as strong as the Anarchist. His muscles were much less developed than the Philosopher’s. “We need someone like him.” The Anarchist indicated the Idiot.

“The Philosopher didn’t trust the Anarchist, but at least their objectives were the same. They had discussed their plan between sets in the prison gym.”

The Pervert was not capable of carrying as much as the Idiot, who was thickly muscled and built for endurance. But at least the Pervert could hold up his end of a conversation during the long escape. That was more than could be said of the Idiot or even the Anarchist. The Philosopher had hoped for better company.

At night during the planning, the Philosopher lay awake in his cell, muscles aching from his workouts, cortisol coursing through his body, and he thought about the deprivation they would endure. As he began to fully consider the challenges of the scorching tundra, he finally grasped the horror of the Anarchist’s plan. The Pervert would not do at all. The Idiot was crucial to their success. The Philosopher didn’t sleep the rest of that night. Yes, it was a difficult thing to contemplate but, if the situation grew desperate, the Philosopher believed he would be able to do what was necessary to survive.

T

heir exposed flesh was dark and raw from near-constant exposure to the sun. The Idiot, always shirtless, had gone from white to pink to red to a ruddied bronze. His body had consumed its fat stores, and muscular detail seared through his skin. The sinews of his shoulders and back made him appear more like a muscle-bound behemoth than an escaped imbecile.

The prisoners were nearly out of water, again. A high mountain range with snow-capped peaks appeared to be about two days to the west. At a higher altitude, they could melt snow, or with luck, they might find a clear stream closer to the base. A day-and-a-half later, they reached the foothills, and this proved to be the case. They refilled their skins from a rushing stream, and the water looked clean enough that, desperate to ease their thirst, they did not bother to boil it before drinking their fill. When none of them got sick, they knew it was pure.

They frolicked in the flowing stream and then camped during the four-hour night, luxuriating in the cool air at elevation. The pleasant breeze made the Anarchist more talkative.

“Did you have a woman?” the Philosopher asked after they had bathed and made camp beside the flowing water.

“Yes,” the Anarchist said.

“What happened to her?”

“Sophia died before I was sent to prison.” The Anarchist plunged his clean knife into the dirt between them.

“The sinews of his shoulders and back made him appear more like a muscle-bound behemoth than an escaped imbecile.”

The Anarchist didn’t ask, but the Philosopher told him the story of Giselle, the woman he had loved—not of Marie, his partner near the end. He had not loved Marie, and Giselle had not loved him, but being with Marie had allowed him to feel, during intense moments, how life with Giselle might have been. They had worked in an underground colony printing pamphlets to combat the New Order’s propaganda. “We were all captured,” he said. “It was much worse for the women.”

The Anarchist pulled his knife from the ground. He looked at it and wiped the silted side across his upper chest. From the Philosopher’s vantage, it appeared as though the Anarchist was slitting his own throat.

“I hope that Giselle made it to the North Shore.”

“Don’t bet on it,” the Anarchist said. He rose and walked to the water’s edge, dipping his knife in the moving water.

When they awoke the next morning, the Philosopher took inventory of his belongings, and he was horrified to discover that three bullets were gone. He was certain he had placed them in his pocket when he had left his bag beside the stream, fearful that one of the other men would take them. At one point, he had divided them into two stashes. Maybe the missing bullets had fallen from his pocket or been washed away by the river’s current. Or had he moved them from one place in his pack to another? He remembered every move he had made with the bullets. He just couldn’t remember their order.

“What’s wrong?” the Anarchist asked, as the Philosopher searched his belongings.

“Nothing,” the Philosopher said. “I was looking for a letter from Giselle, but I can’t find it.” The Anarchist watched him for several seconds before turning away.

They followed the stream out of the foothills, down to the tundra, hoping it would flow directly to the North Shore and lead them to paradise. As they walked toward the flat landscape ahead of them, the flow of water took a bend to the north, raising their hopes, stirring the Idiot into a frenzy of grunts and wheezes.

“From the Philosopher’s vantage, it appeared as though the Anarchist was slitting his own throat.”

They continued to follow the stream. Then, over the horizon, around a cleft in the rocky landscape, the water trickled out onto a dirt plain, where it turned into a sludgy wallow that ended in a sundried riverbed. They followed the snaking turns left by the previous flow of water for two days, but eventually all visible traces of the river’s past were eradicated by the expanse of landscape ahead.

The side trip felt like an accomplishment with their skins replenished, but it had cost them much of their remaining food. The Idiot’s burlap bags were nearly empty, yet still he held one in each hand.

T

he Anarchist tried to convince the large man to combine their remaining food into one bag so that he could carry more than just his share of their fresh water supply, but the Idiot jerked his forearms out of the Anarchist’s grip, roaring with indignation. The Philosopher and the Anarchist gave up, bearing the heavy load of water themselves.

The Philosopher saw them first: tiny specks moving across the deepest part of the vast valley that the men were approaching. A herd of caribou.

The landscape was almost barren but the ground was solid. They were north of the tundra. The Philosopher surmised that this valley had spent its recent life covered by glaciers that had dug deep to create the bowl before them, shoving the displaced earth onto the surrounding rises, including the one where they stood.

It was rumored that, years before, the Lower Continent, now uninhabitable, had been abundant with crops and a pleasing, cyclical climate. Ancient glaciers had pushed topsoil thousands of miles to the south, allowing this civilization to grow and then thrive for centuries. But the Philosopher kept these thoughts to himself. The New Order punished radical discussions of past climate and geological changes with death, insisting that the earth had always been as it was now.

The Philosopher had maintained a wary friendship with the Revisionist in prison, always concerned that he’d be considered a revisionist, too. Revisionists, convicted, were staked to exposed ground at the beginning of a long day. If they were able to survive that day, they were absolved and set free. None ever had; but they died more honorably than traitors.

In the valley that the men faced, sprigs of new growth burst through the remaining soil. Bushes and clumps of flowering weeds grew from crevices in the rocks, attracting the massive herd of caribou. The Idiot’s nostrils flared with excitement.

The Anarchist clapped the Philosopher on the shoulder and pushed the handgun in his pocket outward so the Philosopher could see its outline. “We’re going to use this soon enough.” he said. But the caribou still lay hours—maybe days—ahead of the men, moving eastward at nearly the same pace they were walking.

“The New Order punished radical discussions of past climate and geological changes with death, insisting that the earth had always been as it was now.”

The Philosopher felt a tremendous burden lift. Saliva moistened his dry mouth, and his tongue flickered over his sun-cracked lips. He hadn’t tasted fresh meat since before he’d been imprisoned. The dried meat in the Idiot’s bag was now nearly inedible due to relentless heat and the microbes it had accumulated.

They walked diagonally toward the herd for the better part of a day. The nimble creatures outpaced them but were seemingly unaware they were being tracked. Eventually, the sun slipped beneath the horizon, and the terrain became too difficult to negotiate in the dusk. The three men were forced to stop for a few hours as the caribou herd moved lazily, steadily away from them.

The men consumed some of their meager, rancid rations. Even at this rate, they only had enough food for a few more days. They would be even more weakened when that was gone, reduced to desperate decisions. The Philosopher drank a couple precious squirts from his skin and rolled over in his bedding with his back to the others.

The Philosopher dreamed of slaughter, a great orgy of bloodletting that led to an endless supply of meat. Then, inexplicably, he was back in the prison gym. Fresh carcasses hung in rows, but the weights, bars, and equipment prevented him from getting to the meat. He lay on a bench, pressing heavy weights for rep after rep, as though this might propel him to sustenance, but it was futile. His muscles engorged, his pectorals and lats grew enormous, but no amount of effort quelled the misery in his belly.

He awoke to light, thinking of Giselle—her tawny legs, the scent of her hair. The dawn broke slowly, the sun’s top edge finally yawning above the horizon. The caribou herd had turned toward the men while they slept.

“We need to split up,” the Anarchist said, matter of fact. “Two of us need to flush them toward the third.”

The Philosopher thought of his reduced supply of bullets and the gun in the Anarchist’s pocket. He didn’t dare confess his loss.

“Why don’t we send the Idiot around the herd and drive them toward us?”

“Because he’s stupid, and he doesn’t know that we have a gun. One of us needs to go with him. ”

The Philosopher thought how to counter this logic, believing the Anarchist wanted him to hand over his bullets and go with he Idiot.

“Are you a good shot?” the Anarchist asked.

“Yes,” the Philosopher said, even though he hadn’t shot at anything since years before he’d been imprisoned.

“Then I’ll give you the gun,” the Anarchist said. “I’m not, but I’m good with a knife.”

The Philosopher felt relief, taking hold of the gun when the Idiot wasn’t looking. The men divided the remnants of their decaying meat supply. The Philosopher placed his allotment in his pack. He already felt sickened by its odor and limp texture. The Idiot filled his now-empty burlap bags with rocks, and then he dropped the last of his rotted meat on top of the new weight. He adjusted his shoulders, making certain the weight was equal.

The Anarchist and the Idiot began their advance around the herd’s eastern flank, the Philosopher watching their figures recede. The two men walked with a discernible distance between them, the Idiot always in the lead, each appearing solitary. The Anarchist gauged the best direction to take, measured by the caribou herd’s movement, and the Idiot followed his lead from the front.

“The dawn broke slowly, the sun’s top edge finally yawning above the horizon.”

As the Idiot and the Anarchist circled around the back of the herd, the southbound caribou moved a little toward the west, still heading toward the Philosopher. He tried to determine where the other men would drive the herd. As dusk began to settle, the shadows lengthened to darkness. The Philosopher walked for two hours, his way partially lit by the moon, more than half full. He stumbled over rocks, knowing he had to make certain he was in range of the herd when they passed him headed south.

When he finally stopped for the night, he was spent and beyond hunger. It was all he could do to sit upright and consume his last bits of rank caribou flesh. He forced himself to swallow without tasting.

T

he sun broke above the horizon a few hours later, and the Philosopher saw that the caribou were only a few kilometers away, heading toward him. He found a rise of rocks that would force part of the herd toward him if they continued on their path. Their emotionless faces would come right at him, and he could shoot them between the eyes. It didn’t matter that he only had four bullets.

The herd slowed, perhaps finding a rich source of weeds, lichen or nettles. Squinting, the Philosopher could see the distant forms of the Idiot and the Anarchist, two fleshy dots on the horizon, making their way around the herd. The Philosopher was practically giddy with the thought of fresh meat and spiritual redemption. One dead caribou would not only sustain the three men for several weeks, it would stave off the necessity of enacting the Anarchist’s soulless plot.

As the sun peaked, the Philosopher found a group of boulders jutting up through the earth’s surface. He chose the largest as his outpost, comfortable to lean against, supporting his forearms as he worked to hold the gun steady. It was hot, but less so than during long days when the sun spun endlessly overhead. The herd was several kilometers away, moving toward him with an escalating urgency that they didn’t understand. They stopped to nibble at fresh vegetation; then, they sprinted ahead, stopping to eat when they saw more succulent shoots, propelled by the contradictory primal forces of fear and sustenance.

“Squinting, the Philosopher could see the distant forms of the Idiot and the Anarchist, two fleshy dots on the horizon, making their way around the herd.”

The Philosopher stepped onto the top of the rock and waved his arms at the two men in the distance, catching the attention of the Anarchist. Now they knew where they needed to drive their prey. The Philosopher sat atop the rock for several minutes, watching the Idiot and the Anarchist split apart, making their final stealthy approach toward the herd to drive them through the small passage between the rocks.

The Philosopher took his place behind the rock, steadying the gun. He pulled the trigger, feeling its impotent force. He needed to feel the pressure and release—unaccustomed as he was to using a gun—before shooting at one of the caribou. Then, he loaded the four remaining bullets into the gun’s chamber.

Finally the charge came. The Anarchist and the Idiot, shouting inhuman sounds and waving their arms, closed in on the herd, funneling it toward the Philosopher. The beasts began to snort and move away from the approaching humans, first walking in annoyance, then scuffling a little faster as the sense of danger increased. As the herd reached full gallop, the stampede converged toward the passage between the rocks, coming at The Philosopher like water through a funnel.

The first beasts passed more than a hundred meters from the Philosopher and, through the thunder of the herd, he could hear the distinct clicking of their tendons slipping over their feet. He fired a shot at the largest buck, a loud cracking sound that resonated over the moving cacophony. Surely, the Anarchist received the message that he was driving the caribou beyond the range of the Philosopher’s gun.

The Anarchist screamed something that sounded more like words than the frightening nonsensical clamor he had made when he and the Idiot had begun their assault on the herd. Then a caribou cow pounded within fifteen 15 meters of the Philosopher’s post. He waited for the beast to turn her head his way. He locked his hands together on the base of the gun, trying to still his forearms. Just as the bullet cracked, the beast ducked her head, her rack of antlers dipping towards the ground as though she had been hit. But she kept on, her hooves thundering and clicking past the Philosopher and into the distance.

He had missed.

His third shot was aimed at a young buck funneled right at him by the Anarchist and the Idiot, now only 200 yards away and closing. The Philosopher fired at the beast at point-blank range. But, at the last second, the buck swerved and the bullet imbedded in his broad flank, a streak of blood zipping past the Philosopher, staining the ground, a mere flesh wound.

The Idiot and the Anarchist continued to bear down on the rock passage with only one caribou between them—this one a smaller, less steady creature. The Philosopher made eye contact with the trembling beast as it charged directly toward him. He could feel its primal fear.

“No!” screamed the Anarchist.

“Just as the bullet cracked, the beast ducked her head, her rack of antlers dipping towards the ground as though she had been hit.”

The wild-eyed beast didn’t notice the large rock that lay between itself and the Philosopher. Its crazed eyes locked on the Philosopher’s. He rose to his full height, arms steady. He pulled the trigger, and the beast’s forehead erupted in bloody carnage. The animal took two more strides as the last signals from its brain reached its limbs. It fell dead near the base of the rock.

The Philosopher felt the deep surge of ecstasy. They would have fresh meat tonight! He sat on the rock and looked into the distance as the last of the herd headed toward the rise south of the men.

“You sonofabitch!” the Anarchist wheezed between breaths, looking up at the Philosopher from the base of the rock. The Idiot stopped several yards away, his chest heaving.

The Philosopher leapt from his perch on the rock. “I got him!” he hooted in glee and tossed his arms into the air, pointing his weapon toward the sky. With his torso extended and gaze upward, the Philosopher absorbed the Anarchist’s unexpected punch in the gut. He doubled over, and the gun clattered from his hand and onto the ground.

“You’re stupider than the Idiot,” The Anarchist said.

The Philosopher placed his hands on the ground to steady himself, the pain of the punch and the momentary collapse of his lungs rendered him silent.

“That animal is poison.”

The Philosopher stood and crossed to the dead caribou. Its open eyes displayed yellowed madness. Foam spewed from its maw and sores decorated its flesh. The beast had advanced-stage tundra madness.

The Philosopher, holding his midsection, sank back onto the ground and placed his other hand on the still-warm neck of the carcass.

“The animal took two more strides as the last signals from its brain reached its limbs. It fell dead near the base of the rock.”

“The herd’s gone, but at least you only shot four bullets.” The Anarchist looked at the southern horizon. “In the morning, we’ll decide whether we should follow the herd south or continue north. Now, give me the gun and the rest of the bullets. I’m a terrible shot, but I’m better than you.”

The Philosopher handed over the gun and confessed that he had lost the other bullets, maybe in the water. the Anarchist turned away, reaching toward the sheath that held his knife, their only remaining weapon.

The Philosopher sat beside the dead beast for more than an hour while the Anarchist and the Idiot consumed the last of their rations. When the tainted corpse of the caribou cooled, the Philosopher stood and crossed to where the Anarchist sat on his bedding, honing his knife across a smooth rock. Darkness descended.

“I couldn’t tell the caribou was sick.”

“I told you ‘no.’” In the light of the nearly full moon, the Philosopher could see the Anarchist was no longer angry.

“We can cut up the animal and eat the clean parts.”

“We’d only die a slower, more painful death.” When the Anarchist finally looked up, the sinewy man’s unflinching eyes were muted by pity.

“What about him?” the Philosopher indicated The Idiot, sleeping 30 yards or so away. The Idiot’s custom had always been to sleep apart from the others except when they found a cave or underground enclave. The other men had no qualms with this arrangement. The Idiot had a stench nearly as aggravating as his inability to communicate.

“What do you mean?” the Anarchist asked, holding up his knife, examining it in the moonlight.

The Philosopher was trying to indirectly communicate that perhaps it was time to enact the Anarchist’s plan. “Back in the gym, we talked about bringing a third man. How, if it came to that…”

The Anarchist set his blade aside. “That’s for extreme circumstances. We have a couple days.” The Philosopher could feel distaste and judgment in the Anarchist’s words. “Let’s get some sleep. We’ll walk to the top of the southern rise in the morning and see if the herd’s still within reach.” The Anarchist tucked his knife into its scabbard at his belly and turned over in his bedding, away from the Philosopher.

“Sure.” The Philosopher felt chastised, but he was only mentioning the Anarchist’s plan. And, if they were on the verge of this moral eventuality, it made sense to proceed now while they still had the strength to overpower the Idiot. In a few days they would be too weak to subdue the larger, stronger man. The Philosopher unrolled his bedding, trying to get comfortable on the scrabbled ground.

He found it hard to sleep, then harder still to contend with his nightmares of hungry desperation. Giselle flickered through his mind, but her glorious form gave way to Marie and her shorter, stockier body; her heavier female scent. Then, his subconscious took him back to the prison gym and, again, the carcasses of beasts hanging in rows. Now, the meat gave off the stench of rot. The weights he tried to lift pinned him in place. Across the room, the carcasses had changed from those of beasts to those of men, their skinned musculature hanging from hooks. The Philosopher continued to struggle, trying to press the barbell that sank slowly to his neck.

“The Philosopher was trying to indirectly communicate that perhaps it was time to enact the Anarchist’s plan.”

He didn’t awaken naturally, but was startled from sleep at dawn by the sensation of a foot pressing into his back. His shoulders arched involuntarily off the ground. He felt a tugging at his hair, a pressure at his throat, and he could see the early morning sky.

The stench of the Anarchist’s breath filled his nostrils, and he felt his body’s warm fluid cascade down his chest. As his body lowered to the ground, he turned his head to the left and his eye met the Anarchist’s. The Philosopher tried to speak through severed vocal chords, but the only response was a bubbly bloodletting at his neck.

“Sorry, old boy,” the Anarchist said. “I always thought it would be the gallows for you.” The Anarchist wiped his bloodied blade on his pants. “Now at least your pathetic life will have some meaning.”

The Philosopher was surprised by the richness and variety of thoughts that flashed through his mind in those last moments, his body no longer capable of movement or speech, eyes unable to blink.

T

he Anarchist worked throughout the morning, cutting, slicing. When he finished with the knife, he was exhausted, famished, and yet unable to bring himself to eat. The meat was too fresh, too close to the life it had been. The Anarchist tried to focus on the Philosopher’s vanity, his foolish obsession with appearance at the expense of function. But even this was not enough. He had to wait for the meat to dry and take another form. The Idiot sat on a rock 50 yards away, looking off to the north, paying little attention to the Anarchist’s industry, merely waiting for him to finish his work.

“The least you could do is help,” the Anarchist said in the Idiot’s direction, knowing that even if the Idiot could hear him, he certainly wouldn’t help. The Idiot had understood well enough what they needed from him when they were planning to escape from the prison. But he had seemed to grow stupider every day after their escape. “You’ll be happy enough to have your fair share, though, won’t you?” the Anarchist wiped the blade across his pants, leaving another wet swatch that blended with all the other stains.

The blade came clean, just as it had after he’d killed Sophia.

“You’ll do it if you love me,” she had said, terror in her eyes as the New Order guards surrounded them. She knew what happened to women in their prisons.

He’d held Sophia close from behind, kissing the back of her neck, his mouth absorbing the last moments of her warm precious flesh. Then he drew his knife deeply across her throat, gasping, sobbing before the guards burst into the room and arrested him.

It was much easier with the Philosopher.

The Anarchist laid the strips of flesh atop the large rock that the Philosopher had used as his blind. The rock was smooth and hot in the sun. The Anarchist estimated that, by the end of the next day, the strips would be dry enough to pack. Lean muscle dried much more quickly than tissue laced with fat.

With the butchering done, the Anarchist sank to the ground, weak from the effort and lack of food. He squirted a small amount of water onto his hands. But they were too stained and caked with blood; he needed much more water than he could spare for them to come clean.

He took a small sip of water, trying to slake his thirst. Finally, the Idiot had moved from his rock. Idiot, he thought. He didn’t care if the Idiot wandered off, never to be seen again. It only meant more fresh meat for him. Flies buzzed around the inedible caribou carcass and the Philosopher’s remains, which he had tossed nearby.

The Anarchist waved a hand in front of his face, brushing away an errant pest, and in so doing noticed a hovering shadow, but he was too tired to turn toward its source. He felt the bludgeon at the back of his head more as numbness than pain. The rock dropped beside him. Then the thick muscled hands of the Idiot were around his throat. The Anarchist reached back but, exhausted from his butchery, all he could do was grasp the forearms that had him from behind, his strength rendered meaningless. The Anarchist’s mind went woozy, and he fought to maintain consciousness as the muscled fingers tightened their grip, crushing his larynx, choking off his life.

T

he Idiot took nearly three days to finish restocking his supplies. He worked steadily toward his single-minded purpose of reaching the North Shore. His mind filled with images paired with pleasant feelings. Pictures of nubile women with full breasts caused a giddy stirring in the center of his being. The idea of succulent berries made his mouth water; the image of clear cool water splashing against his body made his skin prickle. Neither the Philosopher nor the Anarchist came to mind as he packed his burlap sacks with fresh meat.

By the time he finished, the sky was dark and the moon was full. The air was cool and the night sky provided enough light for traveling. The Idiot pooled the remaining water into skins and slung them over his shoulders. He took the three smooth bullets from his pocket, loaded them into the gun and slipped it into his waistband.

Then he squatted down and grasped the handles of the two overstuffed meat bags, one in each hand. He straightened his legs and lifted them off the ground, the weight straining his shoulders, pulling at the thick muscles across his upper back. Tightening his midsection reduced the pressure. He began to walk in the moonlit night.

Pictures of paradise flitted through his brain, and the two packs of meat made the dense muscles of his forearms twitch. The weight felt good. He had trained for this.

Bodybuilding.com Original Fiction: Survival Of The Fittest

No comments:

Post a Comment